Main article: History of geography

The oldest known world maps date back to ancient Babylon from the 9th century BC.[12] The best known Babylonian world map, however, is the Imago Mundi of 600 BC.[13] The map as reconstructed by Eckhard Unger shows Babylon on the Euphrates, surrounded by a circular landmass showing Assyria, Urartu[14] and several cities, in turn surrounded by a "bitter river" (Oceanus), with seven islands arranged around it so as to form a seven-pointed star. The accompanying text mentions seven outer regions beyond the encircling ocean. The descriptions of five of them have survived.[15] In contrast to the Imago Mundi, an earlier Babylonian world map dating back to the 9th century BC depicted Babylon as being further north from the center of the world, though it is not certain what that center was supposed to represent.[12]

The ideas of Anaximander (c. 610 BC-c. 545 BC): considered by later Greek writers to be the true founder of geography, come to us through fragments quoted by his successors. Anaximander is credited with the invention of the gnomon, the simple, yet efficient Greek instrument that allowed the early measurement of latitude. Thales is also credited with the prediction of eclipses. The foundations of geography can be traced to the ancient cultures, such as the ancient, medieval, and early modern Chinese. The Greeks, who were the first to explore geography as both art and science, achieved this through Cartography, Philosophy, and Literature, or through Mathematics. There is some debate about who was the first person to assert that the Earth is spherical in shape, with the credit going either to Parmenides or Pythagoras. Anaxagoras was able to demonstrate that the profile of the Earth was circular by explaining eclipses. However, he still believed that the Earth was a flat disk, as did many of his contemporaries. One of the first estimates of the radius of the Earth was made by Eratosthenes.[16]

The first rigorous system of latitude and longitude lines is credited to Hipparchus. He employed a sexagesimal system that was derived from Babylonian mathematics. The meridians were sub-divided into 360°, with each degree further subdivided 60′ (minutes). To measure the longitude at different location on Earth, he suggested using eclipses to determine the relative difference in time.[17] The extensive mapping by the Romans as they explored new lands would later provide a high level of information for Ptolemy to construct detailed atlases. He extended the work of Hipparchus, using a grid system on his maps and adopting a length of 56.5 miles for a degree.[18]

From the 3rd century onwards, Chinese methods of geographical study and writing of geographical literature became much more complex than what was found in Europe at the time (until the 13th century).[19] Chinese geographers such as Liu An, Pei Xiu, Jia Dan, Shen Kuo, Fan Chengda, Zhou Daguan, and Xu Xiake wrote important treatises, yet by the 17th century advanced ideas and methods of Western-style geography were adopted in China.

During the Middle Ages, the fall of the Roman empire led to a shift in the evolution of geography from Europe to the Islamic world.[19] Muslim geographers such as Muhammad al-Idrisi produced detailed world maps (such as Tabula Rogeriana), while other geographers such as Yaqut al-Hamawi, Abu Rayhan Biruni, Ibn Battuta, and Ibn Khaldun provided detailed accounts of their journeys and the geography of the regions they visited. Turkish geographer, Mahmud al-Kashgari drew a world map on a linguistic basis, and later so did Piri Reis (Piri Reis map). Further, Islamic scholars translated and interpreted the earlier works of the Romans and the Greeks and established the House of Wisdom in Baghdad for this purpose.[20] Abū Zayd al-Balkhī, originally from Balkh, founded the "Balkhī school" of terrestrial mapping in Baghdad.[21] Suhrāb, a late tenth century Muslim geographer accompanied a book of geographical coordinates, with instructions for making a rectangular world map with equirectangular projection or cylindrical equidistant projection.[21][verification needed]

Abu Rayhan Biruni (976-1048) first described a polar equi-azimuthal equidistant projection of the celestial sphere.[22] He was regarded as the most skilled when it came to mapping cities and measuring the distances between them, which he did for many cities in the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent. He often combined astronomical readings and mathematical equations, in order to develop methods of pin-pointing locations by recording degrees of latitude and longitude. He also developed similar techniques when it came to measuring the heights of mountains, depths of the valleys, and expanse of the horizon. He also discussed human geography and the planetary habitability of the Earth. He also calculated the latitude of Kath, Khwarezm, using the maximum altitude of the Sun, and solved a complex geodesic equation in order to accurately compute the Earth's circumference, which were close to modern values of the Earth's circumference.[23] His estimate of 6,339.9 km for the Earth radius was only 16.8 km less than the modern value of 6,356.7 km. In contrast to his predecessors, who measured the Earth's circumference by sighting the Sun simultaneously from two different locations, al-Biruni developed a new method of using trigonometric calculations, based on the angle between a plain and mountain top, which yielded more accurate measurements of the Earth's circumference, and made it possible for it to be measured by a single person from a single location.[24]

The European Age of Discovery during the 16th and the 17th centuries, where many new lands were discovered and accounts by European explorers such as Christopher Columbus, Marco Polo, and James Cook revived a desire for both accurate geographic detail, and more solid theoretical foundations in Europe. The problem facing both explorers and geographers was finding the latitude and longitude of a geographic location. The problem of latitude was solved long ago but that of longitude remained; agreeing on what zero meridian should be was only part of the problem. It was left to John Harrison to solve it by inventing the chronometer H-4 in 1760, and later in 1884 for the International Meridian Conference to adopt by convention the Greenwich meridian as zero meridian.[25]

The 18th and the 19th centuries were the times when geography became recognized as a discrete academic discipline, and became part of a typical university curriculum in Europe (especially Paris and Berlin). The development of many geographic societies also occurred during the 19th century, with the foundations of the Société de Géographie in 1821,[26] the Royal Geographical Society in 1830,[27] Russian Geographical Society in 1845,[28] American Geographical Society in 1851,[29] and the National Geographic Society in 1888.[30]The influence of Immanuel Kant, Alexander von Humboldt, Carl Ritter, and Paul Vidal de la Blache can be seen as a major turning point in geography from a philosophy to an academic subject.

Over the past two centuries, the advancements in technology with computers have led to the development of geomatics. and new practices such as participant observation and geostatistics being incorporated into geography's portfolio of tools. In the West during the 20th century, the discipline of geography went through four major phases: environmental determinism, regional geography, the quantitative revolution, and critical geography. The strong interdisciplinary links between geography and the sciences of geology and botany, as well as economics, sociology and demographics have also grown greatly, especially as a result of Earth System Science that seeks to understand the world in a holistic view.

Notable geographers[edit]

Main articles: List of geographers and List of Graeco-Roman geographers

- Eratosthenes (276BC - 194BC) - calculated the size of the Earth.

- Strabo (64/63 BC – ca. AD 24) - wrote Geographica, one of the first books outlining the study of geography.

- Ptolemy (c.90–c.168) - compiled Greek and Roman knowledge into the book Geographia.

- Al Idrisi (Arabic: أبو عبد الله محمد الإدريسي; Latin: Dreses) (1100–1165/66) - author of Nuzhatul Mushtaq.

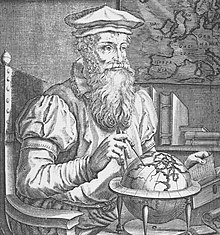

- Gerardus Mercator (1512–1594) - innovative cartographer produced the mercator projection

- Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) - Considered Father of modern geography, published the Kosmos and founder of the sub-field biogeography.

- Carl Ritter (1779–1859) - Considered Father of modern geography. Occupied the first chair of geography at Berlin University.

- Arnold Henry Guyot (1807–1884) - noted the structure of glaciers and advanced understanding in glacier motion, especially in fast ice flow.

- William Morris Davis (1850–1934) - father of American geography and developer of the cycle of erosion.

- Paul Vidal de la Blache (1845–1918) - founder of the French school of geopolitics and wrote the principles of human geography.

- Sir Halford John Mackinder (1861–1947) - Co-founder of the LSE, Geographical Association

- Ellen Churchill Semple (1863–1932) - She was America's first influential female geographer.

- Carl O. Sauer (1889–1975) - Prominent cultural geographer

- Walter Christaller (1893–1969) - human geographer and inventor of Central place theory.

- Yi-Fu Tuan (1930-) - Chinese-American scholar credited with starting Humanistic Geography as a discipline.

- Karl W. Butzer (1934-) - An influential German-American geographer, cultural ecologist and environmental archaeologist.

- David Harvey (1935-) - Marxist geographer and author of theories on spatial and urban geography, winner of the Vautrin Lud Prize.

- Edward Soja (1941-2015) - Noted for his work on regional development, planning and governance along with coining the terms Synekism and Postmetropolis, winner of the Vautrin Lud Prize.

- Michael Frank Goodchild (1944-) - prominent GIS scholar and winner of the RGS founder's medal in 2003.

- Doreen Massey (1944-2016) - Key scholar in the space and places of globalization and its pluralities, winner of the Vautrin Lud Prize.

- Nigel Thrift (1949-) - originator of non-representational theory.

Institutions and societies[edit]

- American Geographical Society (U.S.)

- Anton Melik Geographical Institute (Slovenia)

- Association of American Geographers (AAG)

- National Geographic Society (U.S.)

- Royal Canadian Geographical Society (Canada)

- Royal Geographical Society (UK)

- Russian Geographical Society (Russia)

- Royal Danish Geographical Society (Denmark)

No comments:

Post a Comment